An Epilogue for

a Relationship

Type

Self-Initiated Work

Details

A Master’s Thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts

Aalto University

School of Arts, Design and Architecture

Department of Media

Visual Communication Design

Tags

Editorial Design

Illustration

Academic Writing

Year

2022

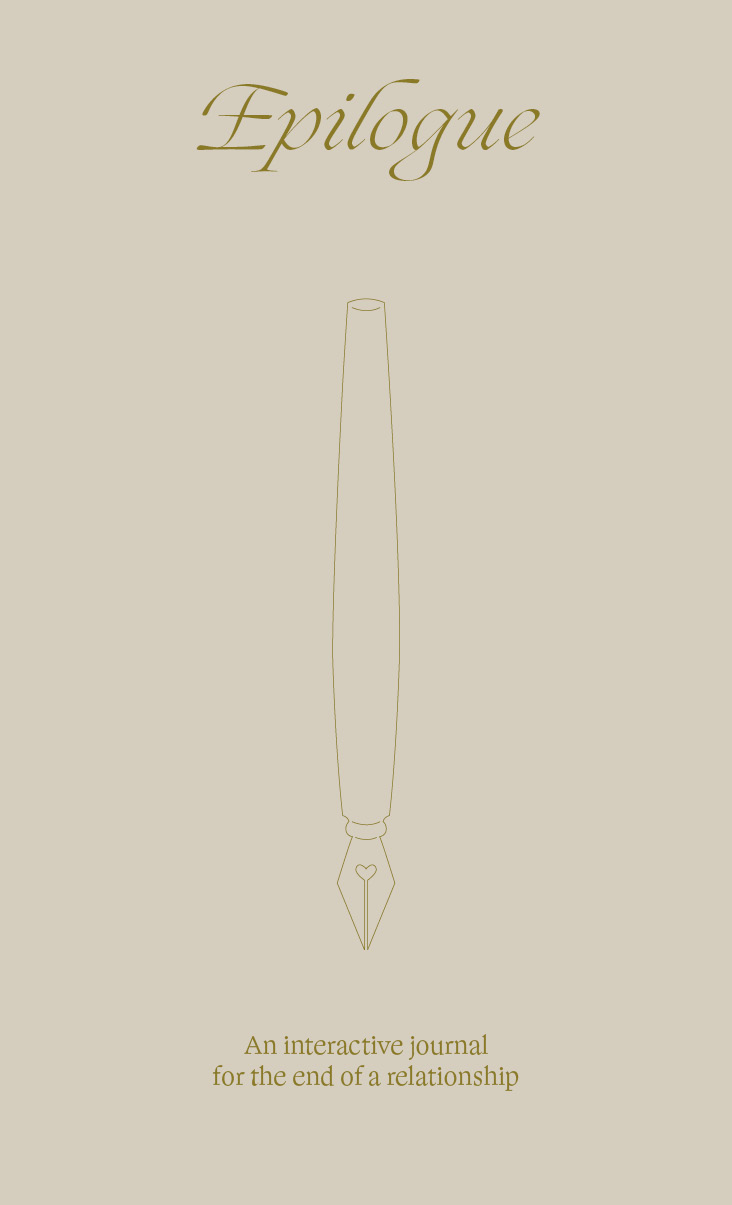

An Epilogue for a Relationship is my Master’s Thesis, done for the Visual Communication Design program at Aalto University. It was inspired by the dissolution of an 11-year-long relationship, the questions I had following that cataclysmic event, and the places I turned to for answers. In short, the thesis deals with self-help literature: its origins, its ubiquity throughout history, and how it’s been viewed—or ignored—by the scientific community throughout the ages. It analyzes a specific subgenre of self-help, works with writing assignments for the reader, through the lens of toxic positivity.

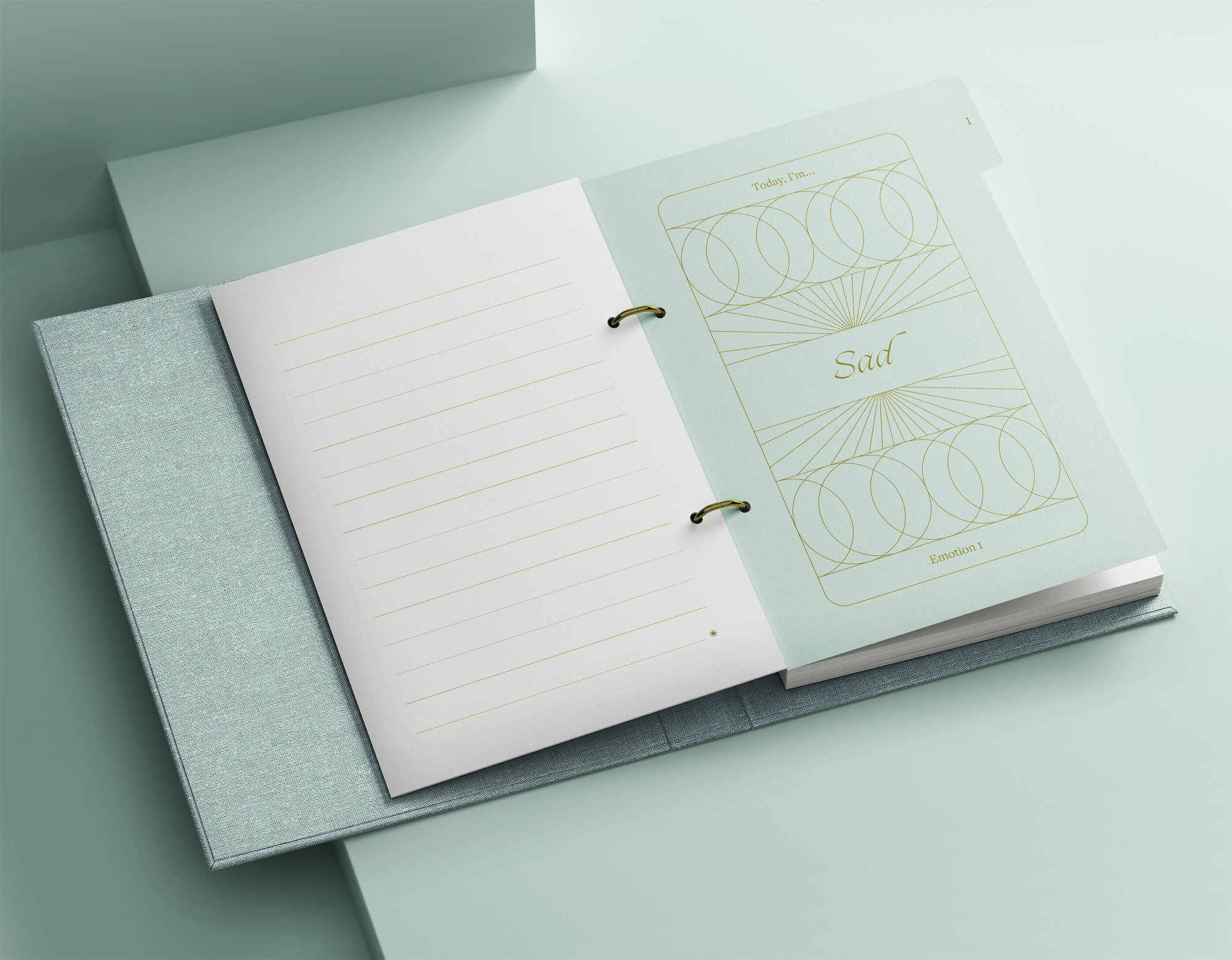

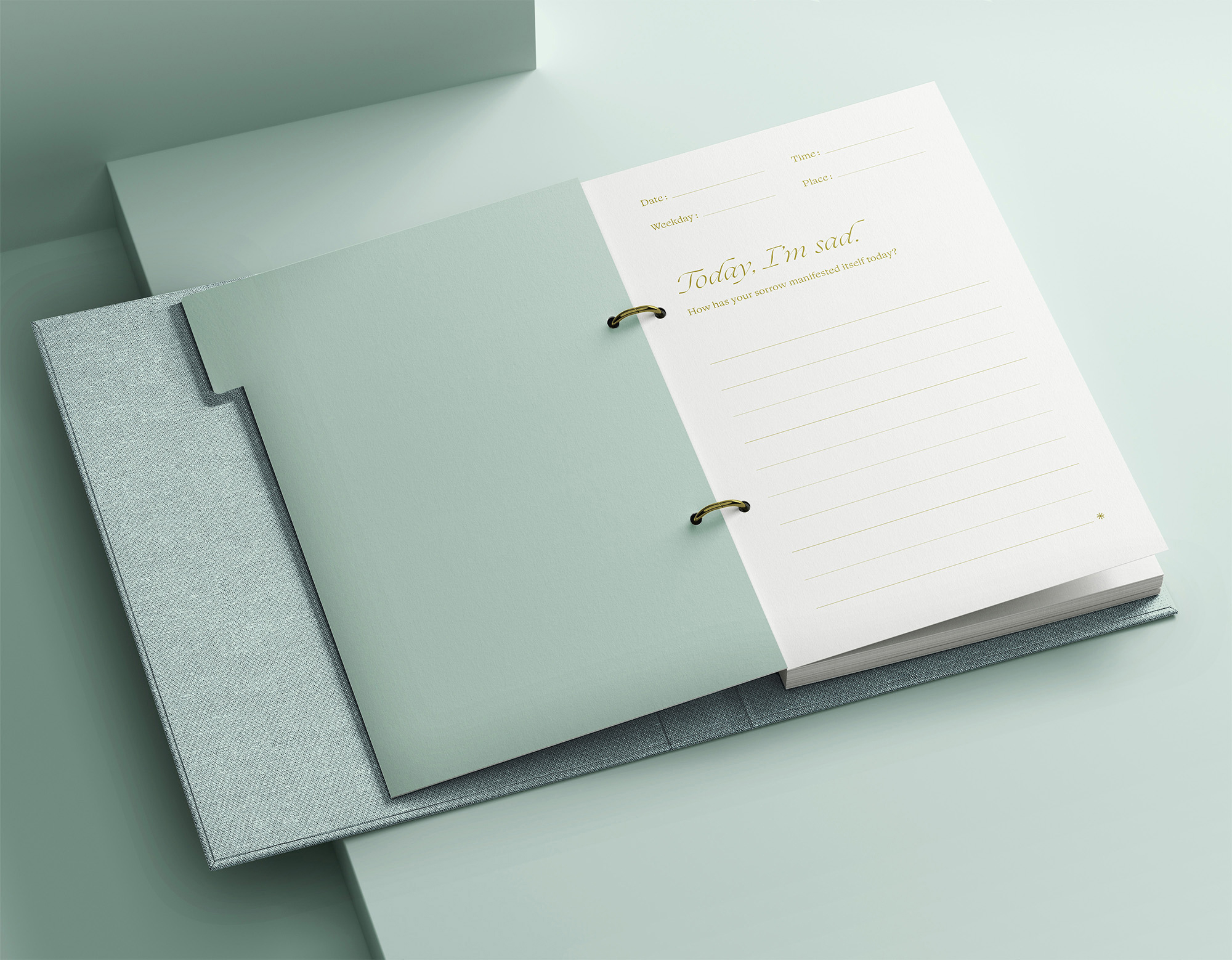

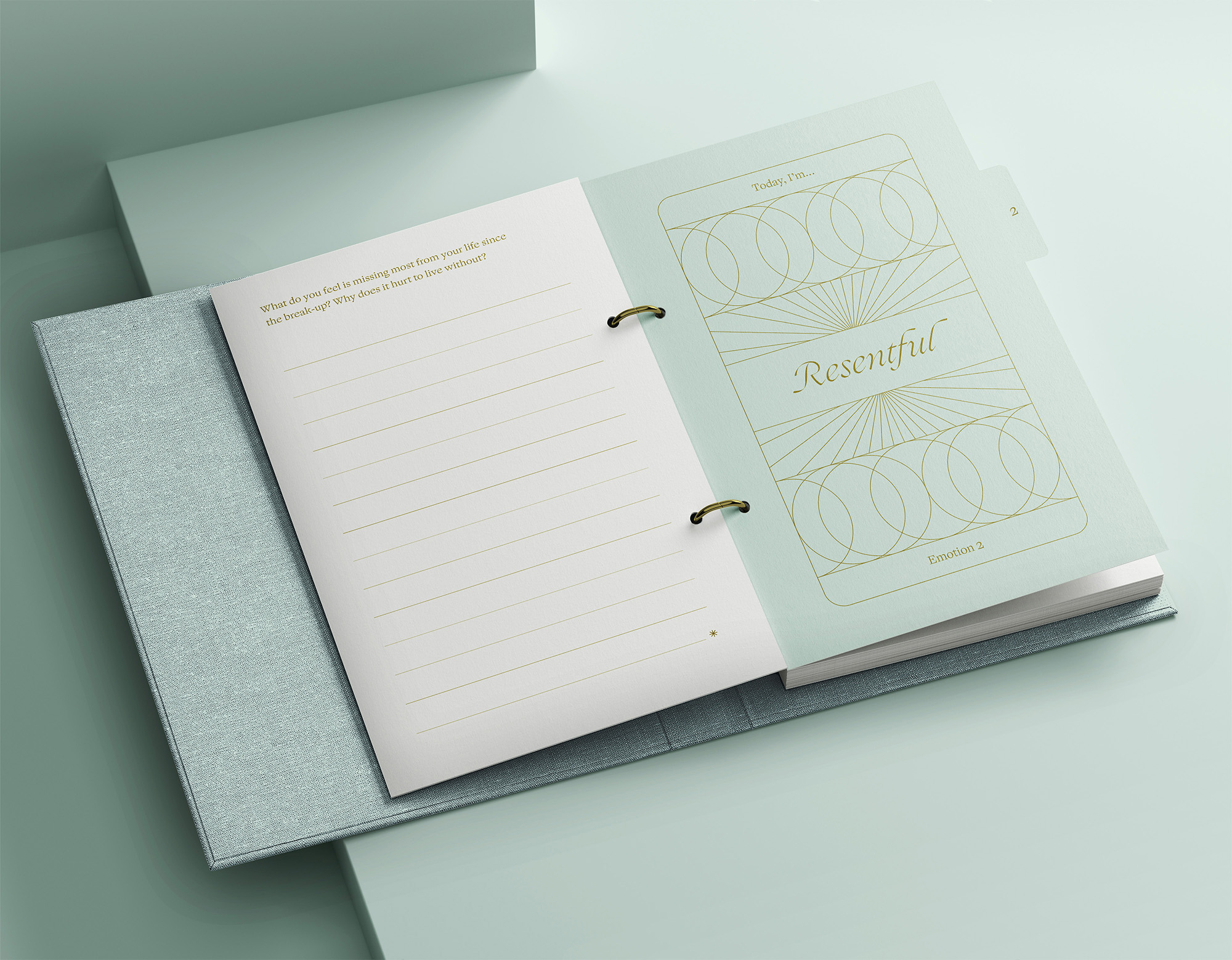

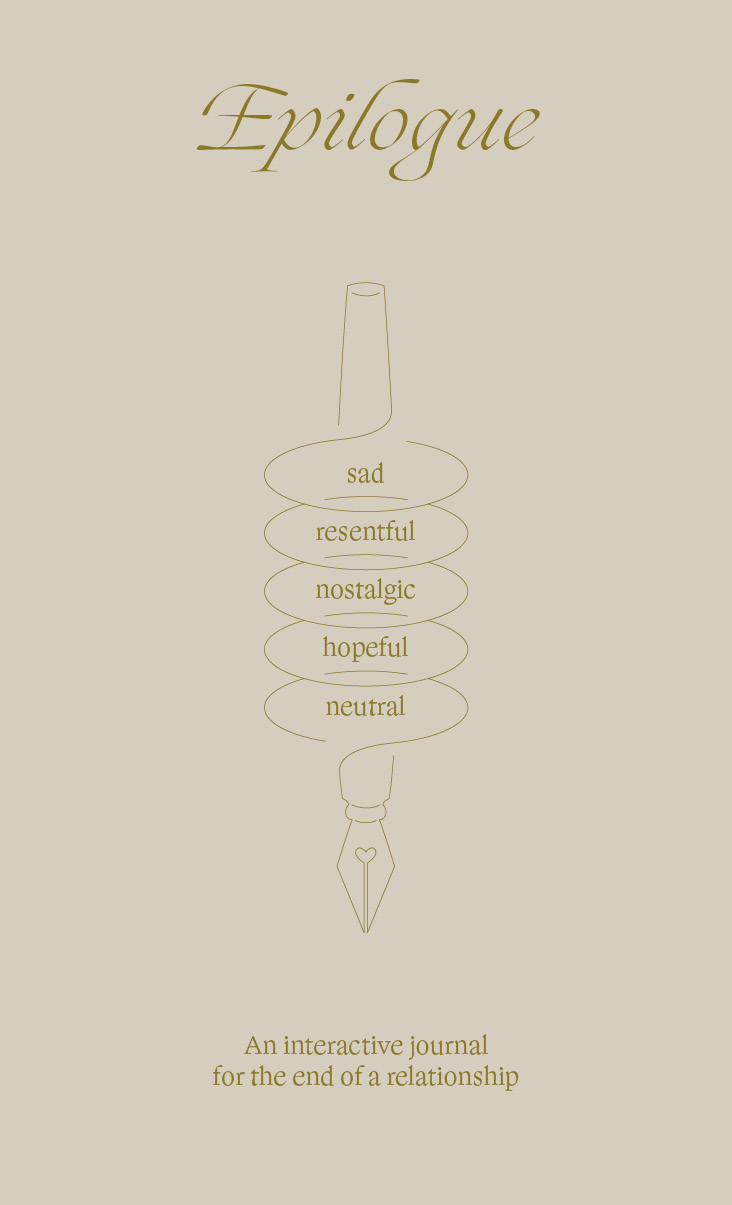

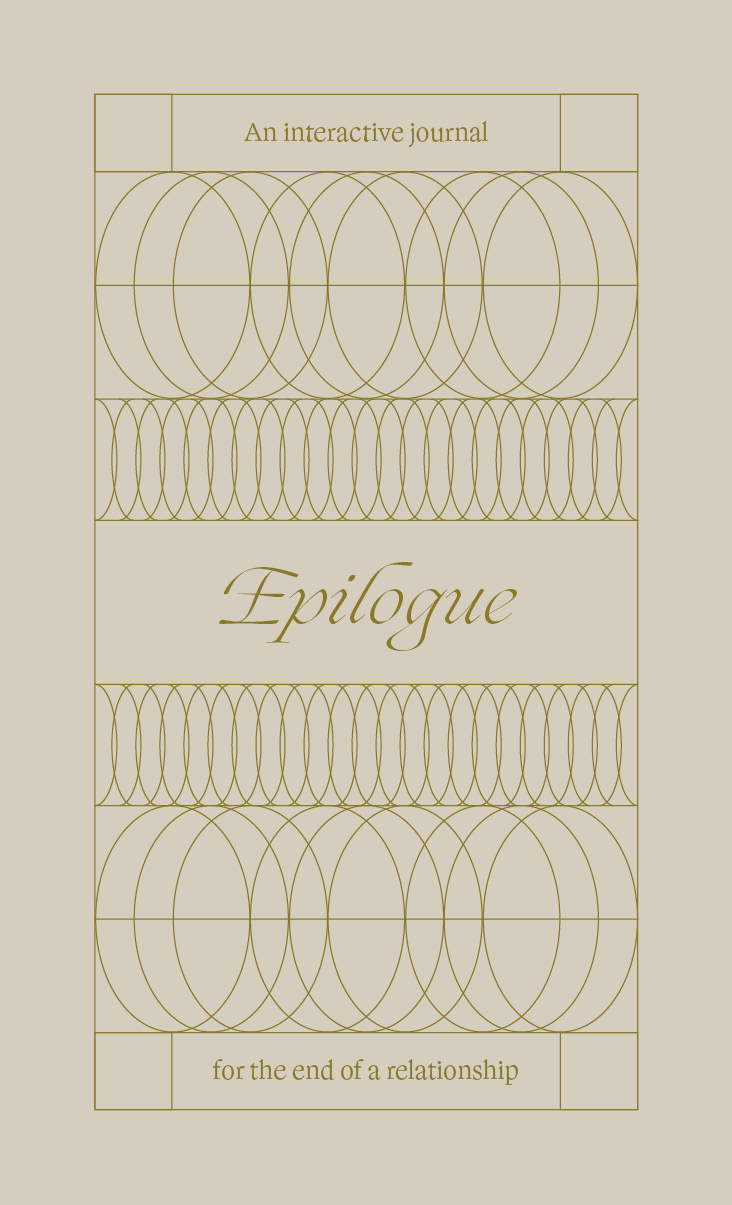

I first categorized and analyzed the current products being sold in my native Finland to find out if and how they were visually signaling their optimism. Then, for the practical part of my thesis, I designed a prototype for a ‘break-up journal’, which attempts to sidestep overt signals of positivity and remain neutral in its emotional expression. The journal is split into five separate emotions (Sad, Resentful, Nostalgic, Hopeful, and Neutral), based on a crude estimation of the different emotions I was feeling when dealing with my own break-up. It has pre-written writing prompts tailored for each emotion, and comes in a ring-bound folder so that the user can move the pages forward freely after writing in order to keep the journal chronological.

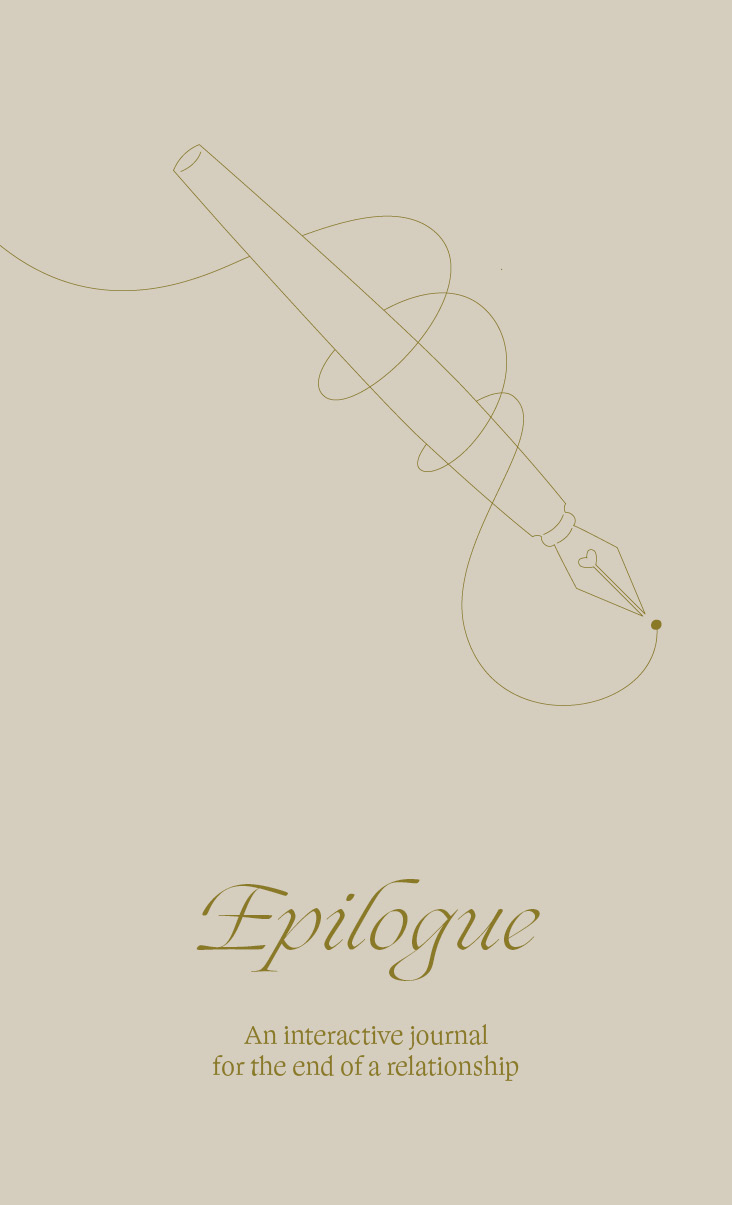

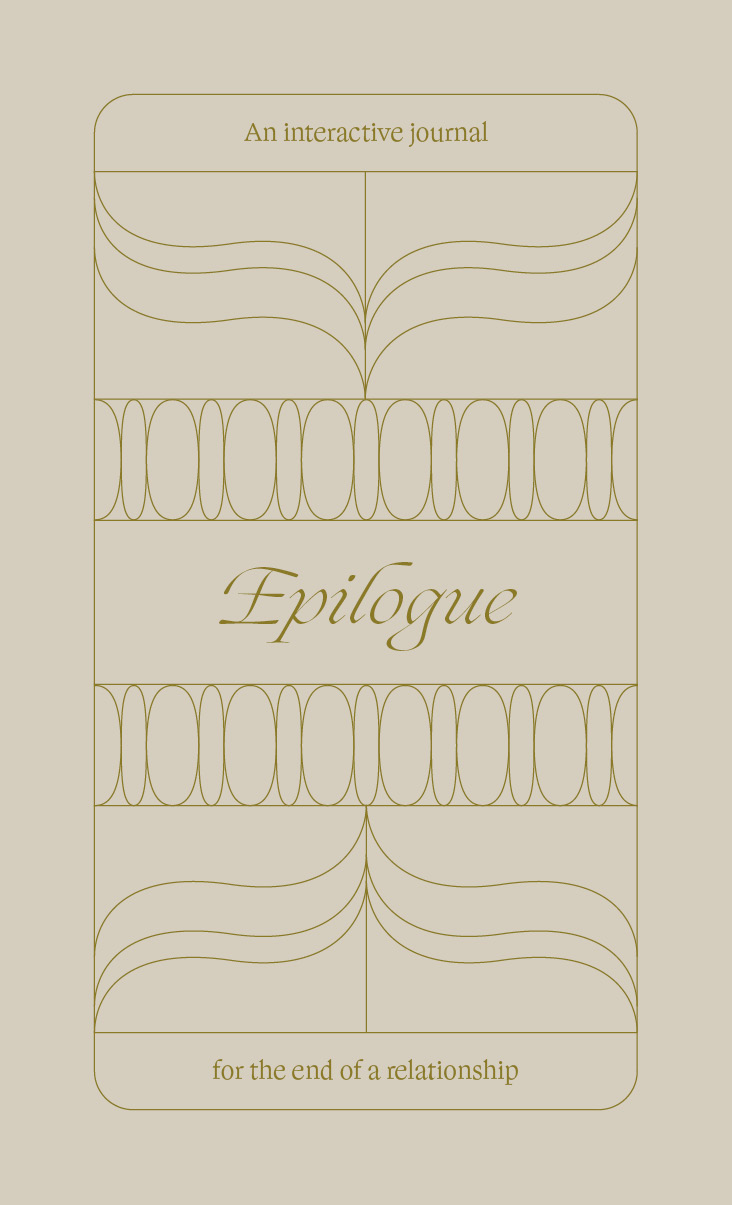

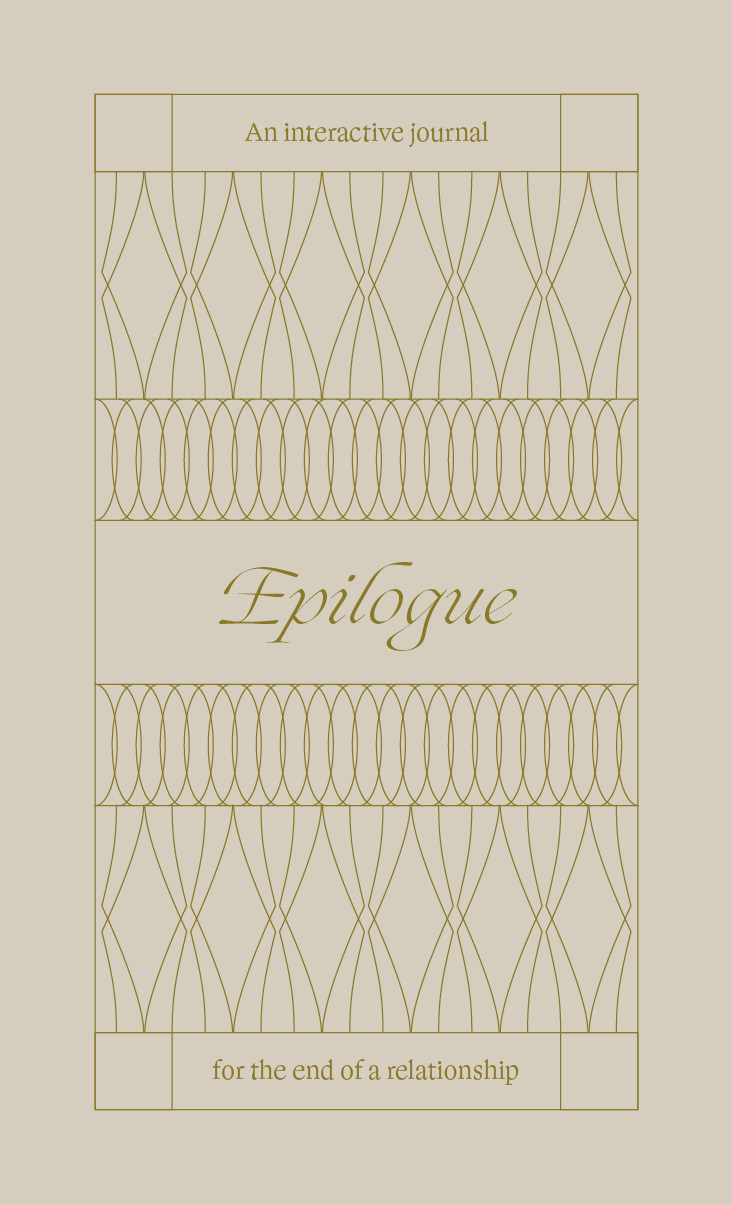

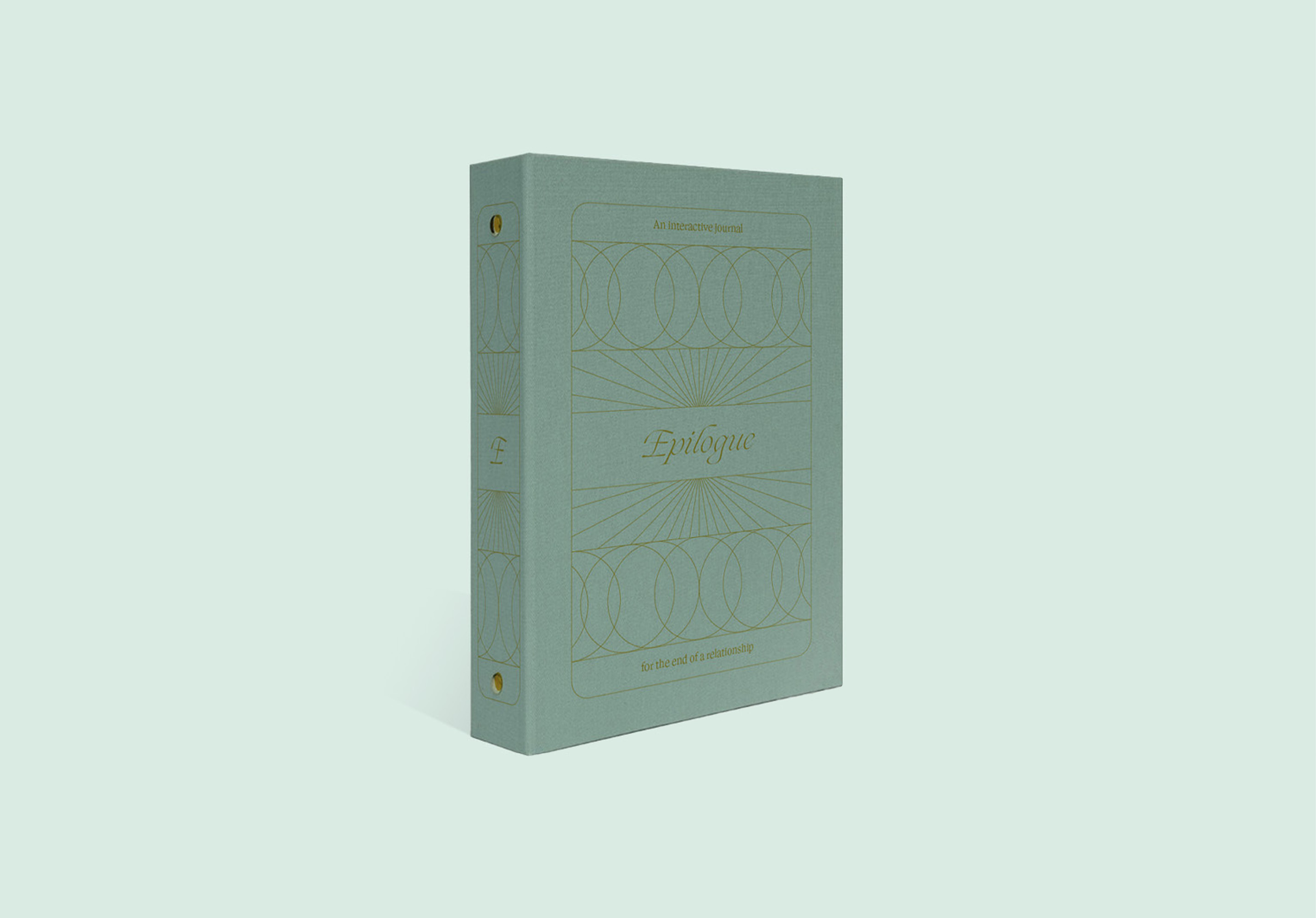

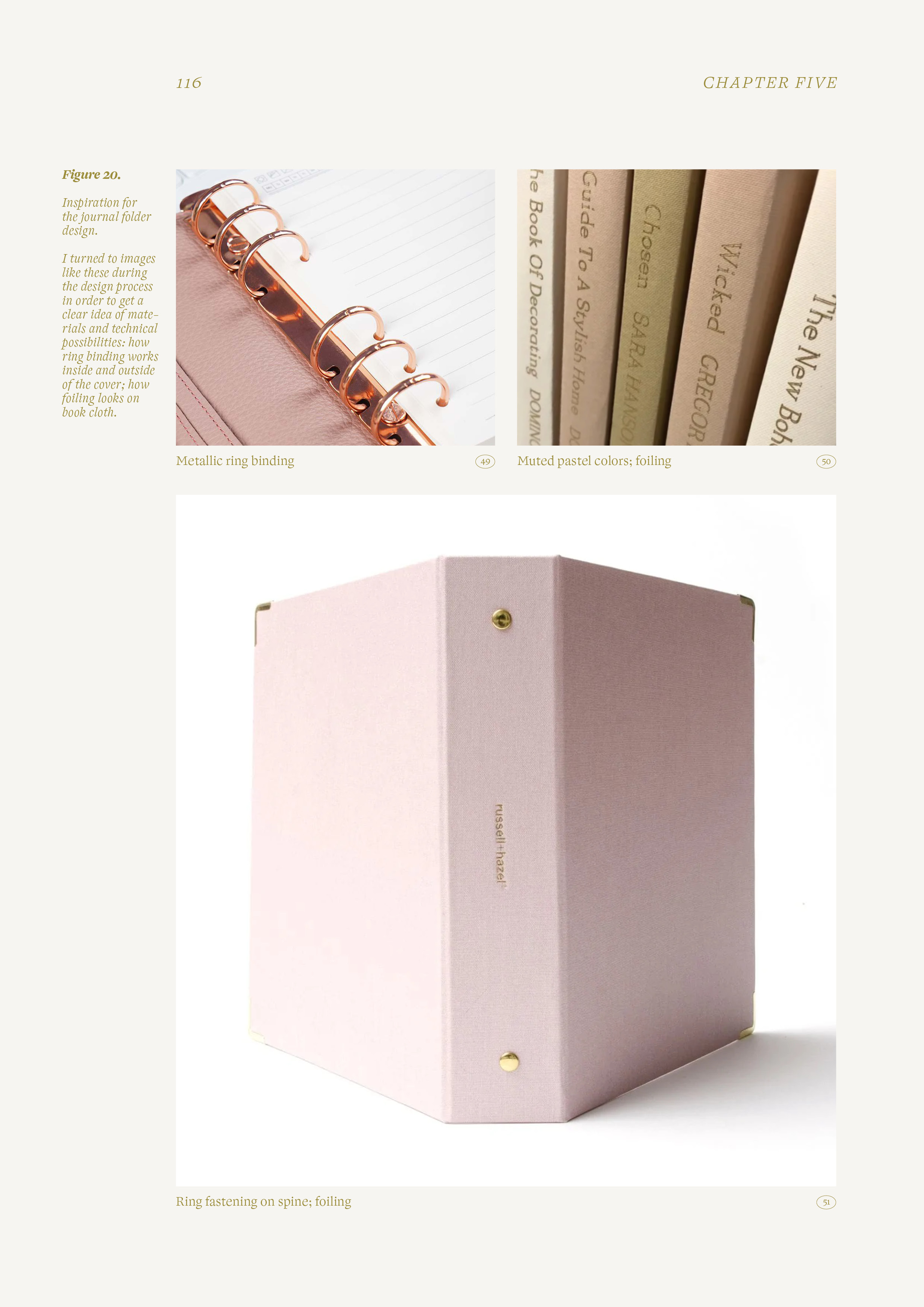

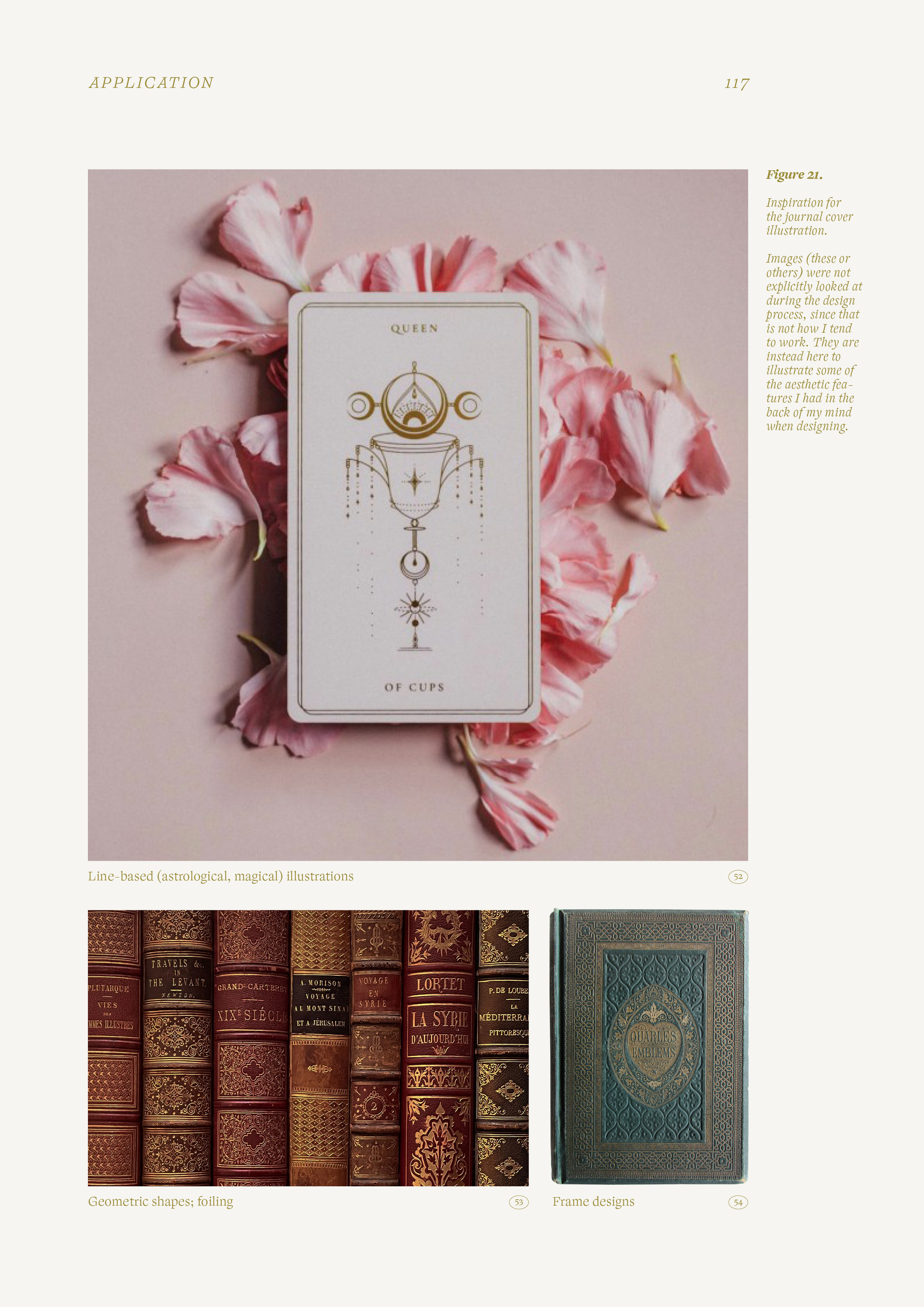

I started the design process, as I often do, by thinking about the concepts of heartbreak and journaling, and my associations with them. Concrete objects such as pens, scribbles, notebooks, and papers were the first to come to mind, so I drew those, but none seemed to convey the neutrality I was after. Eventually, I shifted my mind from the concrete to the abstract. I thought about what I associate with the mood I want my journal to convey: timeless, elegant, charming. The leather- and clothbound and gold-foiled book covers of old came to mind. Often, those did not have any descriptive scenes on them, but instead relied on ornaments and geometric shapes to create interesting frames on the cover and spine. What would it look like if I tried to modernize these visuals? The finalized design, inspired by astrological motifs as a nod to the passing of time, is distinctly different from the products currently on Finnish shelves, while adhering to genre conventions enough to appeal to its target audience.

In addition to my visual work, I’ve also included the background chapter, which details the rise of self-help literature, as an example of my command of both academic writing and the English language. My thesis was given the highest grade by its evaluators.

An Epilogue for a Relationship

Type

Self-Initiated Work

Details

A Master’s Thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts

Aalto University

School of Arts, Design and Architecture

Department of Media

Visual Communication Design

Tags

Editorial Design

Illustration

Academic Writing

Year

2022

An Epilogue for a Relationship is my Master’s Thesis, done for the Visual Communication Design program at Aalto University. It was inspired by the dissolution of an 11-year-long relationship, the questions I had following that cataclysmic event, and the places I turned to for answers. In short, the thesis deals with self-help literature: its origins, its ubiquity throughout history, and how it’s been viewed—or ignored—by the scientific community throughout the ages. It analyzes a specific subgenre of self-help, works with writing assignments for the reader, through the lens of toxic positivity.

I first categorized and analyzed the current products being sold in my native Finland to find out if and how they were visually signaling their optimism. Then, for the practical part of my thesis, I designed a prototype for a ‘break-up journal’, which attempts to sidestep overt signals of positivity and remain neutral in its emotional expression. The journal is split into five separate emotions (Sad, Resentful, Nostalgic, Hopeful, and Neutral), based on a crude estimation of the different emotions I was feeling when dealing with my own break-up. It has pre-written writing prompts tailored for each emotion, and comes in a ring-bound folder so that the user can move the pages forward freely after writing in order to keep the journal chronological.

I started the design process, as I often do, by thinking about the concepts of heartbreak and journaling, and my associations with them. Concrete objects such as pens, scribbles, notebooks, and papers were the first to come to mind, so I drew those, but none seemed to convey the neutrality I was after. Eventually, I shifted my mind from the concrete to the abstract. I thought about what I associate with the mood I want my journal to convey: timeless, elegant, charming. The leather- and clothbound and gold-foiled book covers of old came to mind. Often, those did not have any descriptive scenes on them, but instead relied on ornaments and geometric shapes to create interesting frames on the cover and spine. What would it look like if I tried to modernize these visuals? The finalized design, inspired by astrological motifs as a nod to the passing of time, is distinctly different from the products currently on Finnish shelves, while adhering to genre conventions enough to appeal to its target audience.

In addition to my visual work, I’ve also included the background chapter, which details the rise of self-help literature, as an example of my command of both academic writing and the English language. My thesis was given the highest grade by its evaluators.

An Epilogue for a Relationship

Type Self-Initiated Work

Details A Master’s Thesis Submitted for the degree of Master of Arts

Aalto University

School of Arts, Design and Architecture

Department of Media

Visual Communication Design

Tags Editorial Design, Illustration, Academic Writing

Year 2022

An Epilogue for a Relationship is my Master’s Thesis, done for the Visual Communication Design program at Aalto University. It was inspired by the dissolution of an 11-year-long relationship, the questions I had following that cataclysmic event, and the places I turned to for answers. In short, the thesis deals with self-help literature: its origins, its ubiquity throughout history, and how it’s been viewed—or ignored—by the scientific community throughout the ages. It analyzes a specific subgenre of self-help, works with writing assignments for the reader, through the lens of toxic positivity.

I first categorized and analyzed the current products being sold in my native Finland to find out if and how they were visually signaling their optimism. Then, for the practical part of my thesis, I designed a prototype for a ‘break-up journal’, which attempts to sidestep overt signals of positivity and remain neutral in its emotional expression. The journal is split into five separate emotions (Sad, Resentful, Nostalgic, Hopeful, and Neutral), based on a crude estimation of the different emotions I was feeling when dealing with my own break-up. It has pre-written writing prompts tailored for each emotion, and comes in a ring-bound folder so that the user can move the pages forward freely after writing in order to keep the journal chronological.

I started the design process, as I often do, by thinking about the concepts of heartbreak and journaling, and my associations with them. Concrete objects such as pens, scribbles, notebooks, and papers were the first to come to mind, so I drew those, but none seemed to convey the neutrality I was after. Eventually, I shifted my mind from the concrete to the abstract. I thought about what I associate with the mood I want my journal to convey: timeless, elegant, charming. The leather- and clothbound and gold-foiled book covers of old came to mind. Often, those did not have any descriptive scenes on them, but instead relied on ornaments and geometric shapes to create interesting frames on the cover and spine. What would it look like if I tried to modernize these visuals? The finalized design, inspired by astrological motifs as a nod to the passing of time, is distinctly different from the products currently on Finnish shelves, while adhering to genre conventions enough to appeal to its target audience.

In addition to my visual work, I’ve also included the background chapter, which details the rise of self-help literature, as an example of my command of both academic writing and the English language. My thesis was given the highest grade by its evaluators.

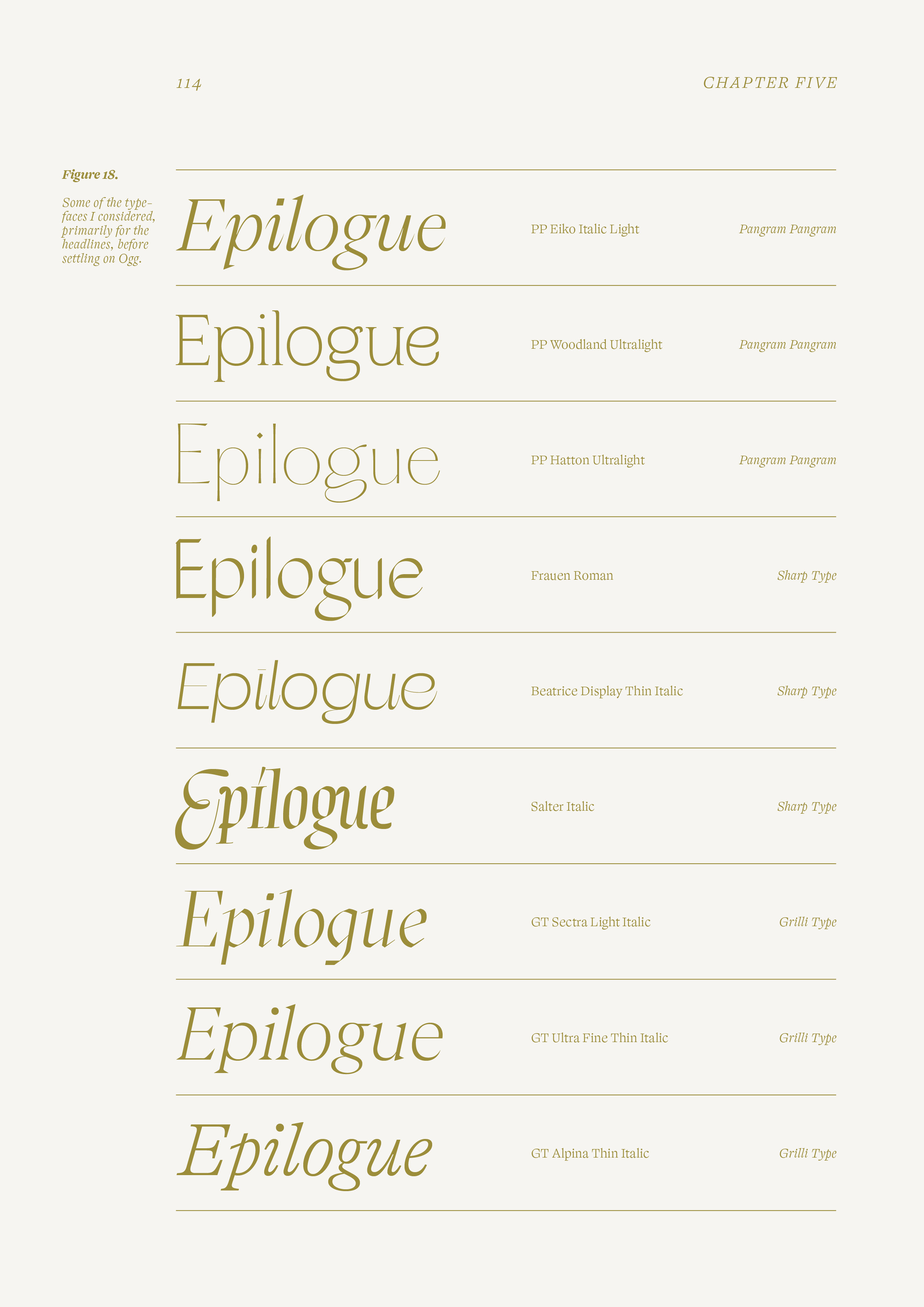

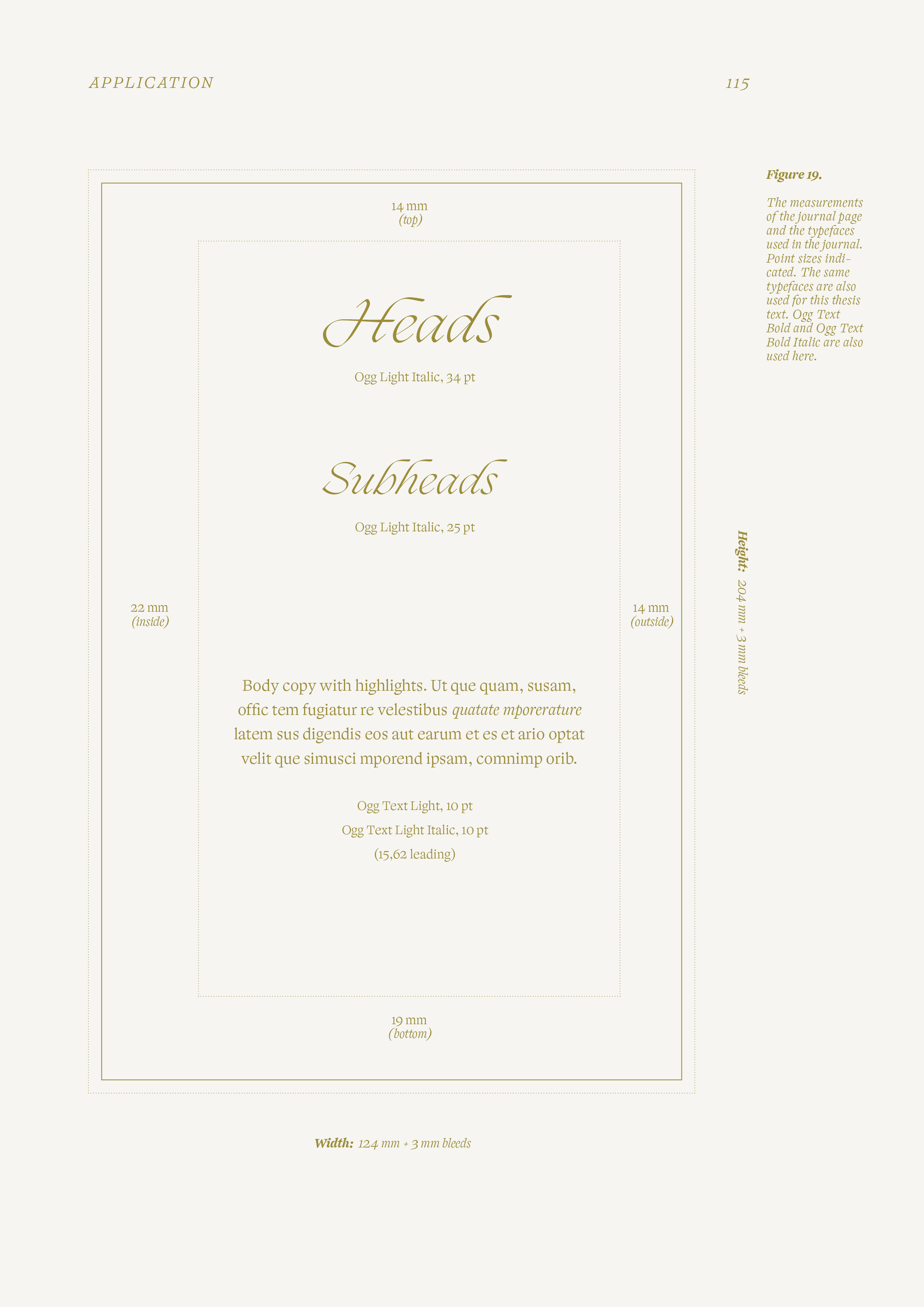

Above: Four pages from my thesis. The first shows examples of typefaces I considered; the second show the journal’s page dimensions; the third and fourth show some of my sources of inspiration for the journal’s design.

Above: Six sketches (small images) of the cover—three concrete ones depicting fountain pens and three abstract ones inspired by book leaves, theater curtains, and world maps respectively—and the final cover design (large image) submitted for evaluation with my thesis.

Chapter 2

Background

This is an excerpt from my Master’s Thesis,

titled “An Epilogue for a Relationship:

Creating a Self-Help Journal Devoid of Toxic Positivity”

In order to map out the development of self-help as a literary genre, it is first important to explain what the term ‘self-help’ means. The precise wording varies, but dictionaries generally define it as the activity of overcoming one’s issues without the help of other individuals or institutions (Cambridge, n.d.; Collins, n.d.; Merriam-Webster, n.d.-a). For the purposes of this thesis, self-help books are defined as works that guide their readers through this process of introspection and independent action. They provide thoughts and instructions, either direct or implied, on the ways in which people should think, act, and live. Modern self-help books and their ancestors can be banded together under the descriptive umbrella term advice literature (e.g., Allen, 2019, paras. 1–2).

Works of advice literature, often discussing proper etiquette or the way to lead ‘the good life’, have been present throughout history and the world (Lamb-Shapiro, 2013). Their origins can be traced as far back as Ancient Egypt, where texts in the sebayt genre offered lessons and guidance in life (Lamb-Shapiro, 2013). In Spring and Autumn Period China, Sun Tzu penned his still-influential work The Art of War, a guide for military officers that makes an extensive case for the importance of their moral character (McCann, 2012). Sun Tzu’s contemporary, social philosopher Confucius, reshaped the concept of junzi or ‘exemplary person’ (Song & Jiao, 2018, p. 1173). Confucius advocates self-transformation through self-mastery and the quest for wisdom and maturity, the goal of which is to gain personal agency and to become a “responsible citizen” (Song & Jiao, 2018). At the dawn of the Common Era, Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius wrote Meditations, a set of personal notes which outline his Stoic “self-therapy” and his thoughts on morality (Ker, 2000, p. 116). The aforementioned works are just a few famous examples of ancient advice literature, which illustrate the age and breadth of the genre. Life advice is inextricably tied to time and place, however. As society evolves, so do its instruction manuals. Since this thesis is concerned with a modern, Finnish take on the genre, a deeper look into more recent Western developments is warranted.

Early Western Advancements

In Europe, advice literature first burgeoned in the Middle Ages. Medieval and Renaissance works can be split into two broad (and hazily defined) subgenres: conduct books and courtesy books (Krueger, 2009). Conduct books, as the name implies, advised literate youth on how to conduct themselves in polite society (Krueger, 2009). They were born in the Early Middle Ages and slowly expanded to address not just the inhabitants of royal palaces but also those of bourgeois households (Krueger, 2009). Most of them were constructed around the literary device of a wise elder advising an inexperienced youth in the ways of the world, and they often borrowed themes and treatises from a rich variety of historical sources, such as the works of church fathers and classical philosophers (Krueger, 2009). Courtesy books borrowed liberally from the same sources (Krueger, 2009), but dealt specifically with “the etiquette of court” (Ashley & Clark, 2001, p. ix). Both conduct and courtesy books can be further split into several subgenres. For example, mirrors for princes is a prominent subgenre of the conduct book, inspired by the writings of Ancient Greek thinkers such as Aristotle, Plato, and Xenophon (Allen, 2019; Weiler, 2015).

Mirrors for princes, much like the self-help books of today, were written to aid their readers in self-development. Unlike their modern descendants, however, they eschewed appealing to the masses in favor of addressing aristocrats; their aim was to “[outline the] basic principles of conduct for rulers” (Weiler, 2015). Some books in this genre even go as far as to suggest that the fates of all governed people are determined by the moral successes and failures of their governors, putting the onus on leaders to familiarize themselves with and adhere to strict moral codes (Weiler, 2015). The tradition of mirrors for princes continued into the Modern Era. One famous example is The Prince, written in 1513, in which Italian Renaissance philosopher Niccolò Machiavelli presents his view on power and governance from the perspective of a princely ruler (Kleidosty, 2018). Mirrors for princes were limited in their scope and target audience, and were complemented by works with a wider appeal, such as other types of conduct books, and courtesy books.

Perhaps the most famous example of a courtesy book, indeed “by all accounts one of the most popular products of the Italian Renaissance”, is Baldesar Castiglione’s The Book of the Courtier, published in 1528 (Lovett, 2012, p. 589). Castiglione and Machiavelli were contemporaries and had similar literary ambitions, but differed in one key aspect: unlike Machiavelli and many other writers of Renaissance advice literature, who directed their words to rulers, Castiglione broadened the genre’s audience by speaking to the ruler’s many courtiers (Lovett, 2012, p. 590). In The Book of the Courtier, Castiglione discusses the “particular qualities”—inherent and learned—of the “perfect courtier” through several imaginary conversations between real members of high society from Castiglione’s circle (Lovett, 2012, pp. 592–593). There are many reasons as to why this particular book was so successful. Historian Peter Burke states that its dialogic format appealed both to those seeking intellectual stimulation and those looking to be entertained: the former were drawn to its many references to famous thinkers and the latter charmed by its lively writing and anecdotes (Martines, 1997). Castiglione also included a chapter devoted entirely to the “court lady”, which directly addressed and appealed to women (Martines, 1997, p. 1148). This was an unusual choice at the time, and contributed to the book’s massive success (Martines, 1997).

Up to this point, women had had a marginal role within advice literature and had not been treated as the equals of men. Many earlier works did not concern themselves with women at all, since nobles such as feudal leaders and knights, who these books were advising, were exclusively male (Krueger, 2009). Advice literature for women was not novel, but authors tended to distinctly separate the works written for women and for men, often revealing misogynistic views on the subservience of women in the process (Krueger, 2009). This was reflected in their content, as books for women often discussed “appearance and sexual morality” while books for men were more concerned with “public behavior and social standing” (Krueger, 2009, p. xix). In other words, books for men focused on how to be a valuable asset to society and books for women on how to be a valuable asset to men. This difference was in line with the moral core of conduct books, since they were rooted in Christianity and consequently often revealed their clerical authors’ views about women’s “submission and obedience to their husbands” (Krueger, 2009, p. xvii). Castiglione was not immune to this, either. Though he praised women not just for their physical assets but also their mental acuity, he nonetheless wanted them to remain fundamentally feminine and pure. These views, juxtaposed through fictitious dialogue, are illustrated by the following quotes from The Book of the Courtier (1901, p. 183; 1901, p. 175):

- “I say that all the things that men can understand, the same can women understand too; and where the intellect of the one penetrates, there also can that of the other penetrate.”

- “[M]ethinks that in her ways, manners, words, gestures and bearing, a woman ought to be very unlike a man; for just as it befits him to show a certain stout and sturdy manliness, so it is becoming in a woman to have a soft and dainty tenderness with an air of womanly sweetness in her every movement.”

Despite matching his contemporaries’ views on the importance of women’s delicate grace, it can be argued that Castiglione presented an uncharacteristically versatile and thoughtful view of women for his time. Furthermore, through being inclusive (i.e., writing for both women and men simultaneously), he helped pave the way for advice literature becoming a more broadly accessible genre.

Advice literature continued to grow more popular during the 1500s and 1600s, when printing revolutionized the spread of information. During this time, conduct books were among the first ones to be translated and adapted for the ever-expanding literate population (Krueger, 2009). Their influence could be seen in Early Modern Britain (Krueger, 2009), where politeness and manners came to define the times so distinctly that historian Lawrence E. Klein states: “the term ‘polite’ is so idiomatic to the eighteenth century [in Britain], it can be used as an alternative to the adjective ‘eighteenth-century’” (2002, pp. 870–871). In Victorian times, advice literature traditions were kept alive through the wide dissemination of etiquette manuals (Dahmer, 2016, para. 3; Krueger, 2009). The first work of this new style is generally considered to be Charles Day’s Hints on Etiquette, which was published in 1834 (Weller, 2014). Etiquette manuals differed from previous iterations of advice literature in their method: instead of employing prose and intricate literary devices to make their case, like conduct and courtesy books had done, their approach was straightforward and structured (Weller, 2014). Hints on Etiquette, for example, was divided into distinct sections, with each giving tips on a particular topic, such as dinners, dressing, and dancing (Weller, 2014). This systematic way of organizing information has been preserved to this day and is, in fact, characteristic of modern advice literature. Instead of presenting their arguments through imaginary narratives, modern self-help books address their readers in a pragmatic and straightforward way.

The Birth of Modern Self-Help

The nascence of self-help as we currently understand it can be traced back to the mid-1800s. Several texts concerned with the history of self-help literature credit Samuel Smiles’ 1859 book, Self-Help, with popularizing the genre (and, indeed, the term itself) in its contemporary form. One example is Harvard professor Beth Blum’s examination of self-help, which describes Self-Help as an “international sensation” and an “antecedent of the contemporary self-improvement guide” (2020, p. 13). Smiles, a Scottish doctor-turned-journalist-turned-author (Morris, 1981), believed that life’s hardships existed to separate the wheat from the chaff and develop character (The Economist, 2004). In an article noting the centenary of his passing, The Economist suggests that Smiles believed “life was not merely best understood, but also best experienced, as a struggle” (2004). Smiles’ conviction that modest origins and relentless effort bred the best men was evident in his writing: it was the underlying assumption of his bestseller.

At its core, Self-Help is a how-to book on social climbing. It was written for young men and presented them with the then-radical idea that their life did not have to be defined by how it began, but could be bettered through hard work and perseverance (Morris, 1981). Historian R. J. Morris describes the work as “middle-class utopianism” brought on by the political hardships of the petit bourgeoisie in 1840s Britain (1981, p. 108). In the same vein, Beth Blum asserts that the self-help genre emerged at this time because academics were rejecting the ‘ignoble’ practice of reading for improvement in favor of the ‘noble’ practice of reading for enjoyment (2020). She writes: “The literary paradigm points to the emergence of self-help as a defense of a specific mode of reading—for agency, use, well-being, and self-change—that was being expelled from institutional spheres” (2020, p. 8). In other words, the less privileged used any means available to climb the social ladder, while the elites frowned upon those that wished to join their ranks. A book like Self-Help, with its endless lists of industrious, successful men of modest origin (Smiles, 1897), captured the zeitgeist perfectly. In fact, some historians have argued that Smiles’ work upheld a “myth of upward social mobility and the self-made man” which sold middle-class ideals to the working-class man (Morris, 1981, p. 91).

Smiles’ approach to advice literature led to an explosive interest in the genre. Unlike his Medieval predecessors, Smiles was not writing for nobility but for the middle class (The Economist, 2004). Even in Medieval times, conduct and courtesy books were used by a much larger audience than they had been written for, since those of lower social standing viewed them as means to learn the ways of the aristocracy and ascend in status (Ashley & Clark, 2001; Krueger, 2009). Much like Castiglione had opened up the genre to a broader audience than the likes of Machiavelli, Smiles extended his advice more broadly still. It can be surmised that Smiles set a new course for advice literature by embracing its longstanding ‘underground’ use and addressing the aspiring social climber directly. In doing so, he helped give birth to a new subgenre. It is important to note that Smiles was by no means the first to write about self-betterment from an individualistic point of view; many works of a similar nature had already been published in Victorian Britain (Richards, 1982). Some of them were even similarly written for lower-middle-class and working-class audiences (Richards, 1982). But Smiles’ works enjoyed unprecedented success, with Self-Help, for example, being reprinted fifty times by 1901 (Richards, 1982). Presumably, the reason behind Smiles’ explosive popularity was the large pool of potential readers in combination with his encouraging message: everyone can become a better (off) person if they are committed to working hard. Importantly, he also emphasized more than social standing alone. When contrasted with its literary predecessors, the core concept of Self-Help is noticeably more down-to-earth. R. J. Morris states that Smiles “[transformed] self-help from the celebration of material and social success to include moral and intellectual self-fulfilment” (1981, p. 108). These more intangible goals—ones that have more to do with a person’s mental development than their social advancement—are much closer to our modern understanding of the objectives of self-help.

In the decades following the publication of Self-Help, books in the genre homed in further on their newfound, eager audience of working- and middle-class men. Around the turn of the twentieth century, they generally focused on life advice for the average white man and were often simple in concept (Cutruzzula, 2016). Before this, most self-help bestsellers were of European origin, but now the genre slowly began to blossom in its current stronghold: the United States. One of the most prolific and popular authors of this time was an American by the name of Orison Swett Marden (Blum, 2020). Marden, who happened upon a copy of Self-Help when working as hired help, became the embodiment of Smiles’ self-made man by rising from modest beginnings to fame and success (Blum, 2020; Bricklin, 2014). Marden published his first book, Pushing to the Front, in 1894 (Bricklin, 2014). His core message, “character is the poor man’s capital”, appealed to the masses, and the book became a downright phenomenon (Bricklin, 2014, p. 26). Much like Smiles’ before him, Marden’s book was built upon extensive real-life examples of successful people (Marden, 1911). And, indeed, he wrote for and about people, not just men, as evidenced by the following impassioned quote from his book (1911, ch. lx):

- “The very suggestion of woman’s inferiority, that she must stand in the man’s shadow and not get ahead of him, that she does not have quite the same rights in anything that he has, the same property rights, the same suffrage rights; in other words, the whole suggestion of woman’s inferiority, has been a criminal wrong to her.”

Further inspired by Smiles, Marden preached the gospel of the self-made (wo)man and insisted that adversity built character (1911). But where those analyzing Smiles have assigned him a rather grim outlook on life, Marden seems the polar opposite. In Pushing to the Front, Marden emphasizes each person’s attitude, and contends that attributes like “a cheerful disposition” and “unbounded enthusiasm in one’s calling” are fundamental to success (1911, ch. xxxviii). This is especially interesting because the book was written during a severe economic crisis (Bricklin, 2014). One could argue, however, that this is precisely the reason behind its success. It is well-known that people flock to self-help in hopes of gaining a sense of personal agency (e.g., Blum, 2020; Dolby, 2005), so Marden’s optimistic words would likely have struck a chord with many struggling Americans looking to navigate those turbulent times. Instead of waiting for outside forces to bless them with joy, they were suddenly being told that they could take charge and make their own happiness. When framed like this, books like Marden’s seem almost fated to succeed.

Marden was not the only author in these times to bring up the value of a person’s positive outlook. So did actor Douglas Fairbanks, whose 1917 book Laugh and Live is a good example of the simplicity and optimism often seen in advice literature during this time. Laugh and Live, as its name suggests, speaks about the power of positive thinking and quite literally invites its readers to laugh away all their troubles (Cutruzzula, 2016). Fairbanks (1917, para. 11) writes:

- “Laugh and live long—if you had a thought of dying—laugh and grow well—if you’re sick and despondent—laugh and grow fat—if your tendency is towards the lean and cadaverous—laugh and succeed—if you’re glum and “unlucky”—laugh and nothing can faze you—not even the Grim Reaper—for the man who has laughed his way through life has nothing to fear of the future. His conscience is clear.”

An interesting parallel can be drawn between Fairbanks’ work and the modern concept of toxic positivity. “Good vibes only” is, in fact, what Fairbanks is advocating, more eloquent though the wording may be. He is prescribing laughter for every ailment and ignoring the complexity of human emotion. It seems many contemporary critics of self-help see the genre as nothing more than an extension of Fairbanks’ wide-eyed maxim: as shallow and syrupy platitudes peddled by snake oil salesmen (e.g., Bergsma, 2007; Dolby, 2005). Snake oil or not, positive thinking is undeniably a core tenet of modern self-help, especially in the 1900s. In this regard, a relatively straight line can be drawn between Marden, Fairbanks, and one of the biggest names of twentieth-century self-help: Dale Carnegie.

Dale Carnegie: A Giant of the Genre

Dale Carnegie is one of the most famous American self-help authors of all time. He has been called the “father of the self-help movement”, and his works are read and referenced extensively to this day (The Economist, 2013). Carnegie idolized Orison Swett Marden (Blum, 2020), and the two had much in common both personally and professionally. Both rose from humble beginnings to fame and success, both preached to the masses about the importance of a positive attitude, both wrote their pivotal works during times of great economic decline, and both understood that their fellow Americans were downtrodden and needed promises of agency and words of encouragement (Corrigan, 2013). Carnegie’s most famous book, How to Win Friends and Influence People, was published in 1936, in the twilight of the Great Depression (Corrigan, 2013). During these times, society desperately “needed to hear that positive thinking would garner positive results” (Corrigan, 2013). Carnegie theorized that many of the most successful men in history had their personality to thank for their prosperity. The Economist summarizes the central idea of How to Win Friends and Influence People as follows: “With charm, confidence and a good smile, anyone can climb the ladder of success” (2013). Carnegie put men in charge of their own fates and told them that the road to bliss was paved with positivity. Some authors have contended that his fascination with a person’s sunny disposition was a part of a greater societal shift from the Victorian obsession with “moral character and self-denial” to our modern fascination with “consumerism and self-promotion” (Corrigan, 2013). His book offered concrete tips on how to get ahead in a changing working world, where one’s ability to forge social connections was suddenly the best way to succeed professionally (The Economist, 2013). Carnegie argued that people were not creatures of logic, but of emotion, and the key to getting ahead in life was to treat them as such (The Economist, 2013). One could go so far as to say he advocated analyzing and exploiting others’ humanity for personal gain. For this reason, his words were met with aversion as well as acclaim.

While his book was a great commercial success, many critics saw Carnegie’s teachings as cynical: “as if all kindness was lubrication for personal advancement” (The Economist, 2013). Canadian media philosopher Marshall McLuhan even wrote an unpublished 1939 essay called Dale Carnegie: America’s Machiavelli (Blum, 2020)—referring, of course, to the unscrupulous tactics championed by the famous thinker. For Machiavelli, the end always justifies the means, which is why the adjective Machiavellian has come to mean the use of cunning and duplicitous tactics in pursuit of a goal (Merriam-Webster, n.d.-b). McLuhan found How to Win Friends and Influence People “morally malignant”, since it advised its readers to gain “irresponsible power over others” by turning humans’ innate conceitedness against them through flattery (Blum, 2020, p. 107). When it came to cunning and deception, Carnegie practiced as he preached. He was born Dale Carnagey but changed the spelling of his surname in hopes of being associated with the famous industrialist Andrew Carnegie (The Economist, 2013). The jig worked. Despite facing heavy criticism, Carnegie’s works are immensely popular to this day, and have helped shape self-help as a genre.

It is apparent that the positive mantras that permeate the world of self-help today can be traced back to authors such as Orison Swett Marden and Dale Carnegie, who promised their eager audiences that they would get far in life if they worked on themselves and had an optimistic outlook. There is something very American about this message, and it is no coincidence that many of the most successful authors of self-help hail from the United States (Bergsma, 2007). Folklorist Sandra K. Dolby theorizes that there are two key reasons as to why Americans are so perfectly attuned to producing and consuming self-help: the long-standing societal tradition of independence and individualism, and the equally established cultural tradition of “[attending to] moral and spiritual growth” (Dolby, 2005, p. 29). The United States is—both historically and currently—a deeply capitalist and deeply religious country, where each individual is responsible for their own success, and great care is taken to keep in touch with one’s spiritual side. It is no wonder, then, that self-help, with its promises of prosperity, happiness, and personal growth, is so successful there. In fact, media sociologist Steven Starker calls the self-help book “a firm part of the fabric of American culture” and “too pervasive and influential to be ignored” (1989, p. 2). Research points to clear ideological ties between the modern self-help industry and the American way of life. American self-help books can be seen as covert missionaries that are preaching the gospel of capitalism and individualism to the world.

Self-help’s ties to capitalism have not gone unnoticed. Louise Woodstock speaks of the genre morphing during the 1990s, with self-help slowly becoming self-improvement (Salmenniemi & Pessi, 2017). These terms hint at an ideological revolution, with books shifting their focus from the external to the internal; from support to instruction; from the search for satisfaction to the search for excellence. It can be argued, however, that this dichotomy has always been present within self-help. When examining the notable works highlighted in this historical overview, one can infer that most of them offer both support and instruction, albeit at varying ratios. They intend to help the reader (to be happier and more successful, for example) as well as improve them (with regards to morality and attitude, for example). Nevertheless, many researchers note that self-help has become increasingly focused on personal improvement. As Beth Blum puts it: “Self-help has changed a great deal since its early associations with Victorian autodidacts and mutual improvement associations. Its emphasis has shifted from morality to morale, from collective uplift to competitive individualism” (2020, p. 242). Some contemporary academics have categorized the entire genre as an extension of the current Western neoliberal ethos, where the self is seen as a resource that one should develop to maximize personal gain (Salmenniemi & Pessi, 2017).

Self-Help and Modern Society

In their study on how self-help positions the self in relation to our modern society, Suvi Salmenniemi and Anne Birgitta Pessi discuss the ideological differences within the genre. According to them, contemporary self-help books can be placed on a continuum from ‘culture-optimistic’ to ‘culture-pessimistic’. Salmenniemi and Pessi note that many Nordic self-help books are culture-optimistic, in contrast to Anglo-American bestsellers in the genre, which are often culture-pessimistic. In culture-optimistic works, societal structures and interconnectedness are seen as valuable to the self (2017). Nordic self-help books frequently criticize the core tenets of capitalism, such as consumerism, materialism, performance-orientation, and individualism. The focus is on how social relations can bring about happiness. The culture-pessimistic works, on the other hand, view current societal structures and outside authorities as inherently harmful to the self (2017). They point to the present post-industrial reality as the root cause of humanity’s issues: the “simpler times” of the past are romanticized and contrasted with the “straining” lifestyle of today. These works aim to “liberate” the reader; to help them find the “true self” they have lost due to being “conditioned” by society. Here, unlike with culture-optimistic books, the gaze is directed inward. Instead of searching for enlightenment through social relations, these works argue that the solutions to our problems can be found within each of us, and that the key to happiness lies in retreating into ourselves.

These differences, described in detail by Salmenniemi and Pessi (2017) serve to illustrate the nebulous nature of modern self-help. Works within the genre do not present a unified front but are, instead, at odds with each other, all promoting their truth as the ultimate one.

The best-selling self-help books display markedly varied justifications for their respective theses (Salmenniemi & Pessi, 2017). Some rely on logic and base their claims on psychology, some have clear connections to the spiritual through Christianity, Buddhism, or New Age, and some purely champion the power of positive thinking (Salmenniemi & Pessi, 2017). These conclusions are based on a study conducted on Finnish self-help, but there is no reason to think that these findings would not be applicable in an international context, as well, considering how broad and murkily defined the genre is. With a readership so large and diverse, there is ample space—and substantial financial motivation—to cater to all tastes. Despite the differences in rationale, the works also invite comparison. Many scholars see the proclivity for optimism as the unifying factor of self-help (e.g., Blum, 2020).

Salmenniemi and Pessi highlight Rhonda Byrne’s massively popular 2006 book The Secret as the epitome of a culture-pessimistic bestseller that legitimizes its claims through a kind of intangible mysticism, and champions the power of positive thinking (2017). The core concept of The Secret is the so-called ‘Law of Attraction’, which states that whatever energy a person puts out into the world, they will attract more of. If someone focuses on negative occurrences, their life is bound to become more miserable. Conversely, the only way to become happy is to cut negative thoughts out of one’s life. Succeeding in this is painted as transformative: through the power of positive thinking, one can get whatever they want, be it true love, good health, or a million dollars. Salmenniemi and Pessi (2017, p. 7) describe it as follows: “Minuus näyttäytyy vapaasti valittavana ja joustavana materiaalina, jota rationaalinen mieli hallitsee ja ohjaa. Onnellisuuden voi tilata Universumin postimyynnistä.” [The self is seen as a freely determinable and malleable material, which the rational mind governs and steers. You can mail-order happiness from the Universe’s catalogue.] Many argue that Byrne’s influential book led to a wave of starry-eyed optimism and endless navel-gazing, which slowly blossomed into our current culture of toxic positivity (e.g., Connor, 2021; Manson, 2015). Self-help author Mark Manson terms Byrne’s teachings “delusional positive thinking” and states that their logical conclusion is that we always need to be wanting something, which makes us less content with what we currently have (2015). Manson’s objections are backed up by science. As discussed in the Introduction, several studies have shown that suppressing negative thoughts and emotions can be detrimental to a person’s psyche. In Byrne’s domain, negativity is not simply discouraged, it is outright banished. She states, for example, in no uncertain terms, that each person only has themselves to blame if they are unhappy. Hardships simply mean that they have ‘thought wrong’ up until that point in their life, as illustrated by the following quote from The Secret (Burdon, 2020):

- “You can create anything you want, but to do that you must follow the principles of the law [of attraction]. Eliminate all doubt and replace it with the full expectation that you will receive what you are asking for. If you are not receiving what you are asking for it is not the law that has failed. It means that your doubt is greater than your faith.”

The frenzied focus on positivity within self-help has piqued the interest of many researchers. Salmenniemi and Pessi argue that the genre is built upon a paradox, since books vow to help readers break free from ‘incorrect’ ways of thinking while simultaneously trapping them in ‘truths’ of their own making (2017). The self, they argue, then becomes both a problem in need of solving and a “horisontissa häämöttävä paratiisi” [paradise looming on the horizon] (2017, p. 3).

Fortunately, some self-help authors have become cognizant of the inherent dangers of toxic positivity and started to rebel against the concept in their writings. One recent example is the straightforwardly titled Toxic Positivity by Whitney Goodman (2022). It is portrayed as an ‘honest guide’ that helps its readers “own [their] emotions—even the difficult ones” (Penguin Random House, 2022). On publisher Penguin Random House’s website, a blurb describes the book as a “much-needed breath of fresh air in the self-help space” (2022). The quote underlines the novelty of this approach to positivity—especially for self-help in the US. As Kimberly Harrington writes in her review for The Washington Post: “[Goodman] shows that [toxic positivity]’s long been woven into almost every aspect of American culture from this country’s earliest days and is, in many ways, our national religion” (2022). To illustrate the difference in tone, Goodman’s work can be contrasted with the likes of Vex King’s book Good Vibes, Good Life, which, much like The Secret, preaches goal manifestation through positive thinking and places the onus on each individual to overcome whatever hardships they might face through employing ‘the right attitude’ (2018). The contrast is evident in these two quotes:

- “Live a life that challenges you, fulfills you, has meaning, and brings you moments of joy. Open yourself to all emotions and experiences. Discover what you value and follow it until the end, knowing that sometimes life is going to hurt and that’s what makes it worth living.” (Goodreads, 2022a)

- “Ultimately, self-love and raising the level of your vibration go hand in hand. When you make an effort to raise your vibration, you show yourself the love and care you deserve. You’ll feel good and attract good. By taking positive actions and changing your mindset, you’ll manifest greater things.” (Goodreads, 2022b)

Clearly, these two works and their kin send vastly different messages to their readers about what happiness is, how one can achieve it, and whether one can ever even be fully in charge of one’s life satisfaction at any given moment. King’s work is a good example of self-help’s tendency to oversimplify the incredibly complex whole that is a human life. As Goodman’s work suggests, problematizing excessive positivity is, in part, a counterreaction to the feel-good bromides that self-help has historically been associated with and continues to disseminate.

The genre’s fervent idealism has also led to another interesting, recent countermovement. Journalist Will Storr notes the emergence of explicitly pessimistic works, which he labels “this is me, being real, deal with it” guides (Schwartz, 2018). They position themselves as ‘authentic’ alternatives to the genre’s current offerings, exhibit a skepticism towards traditional self-help methods, and are often notably profane—one famous example being Mark Manson’s 2016 bestseller The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck (Schwartz, 2018). In an interconnected world, trends such as these quickly make their way around the globe and are adapted to fit each country’s context and mentality. The study done for this thesis includes two Finnish examples of the pessimistic subgenre: the guided journals Pieni pahan mielen kirja and Vitutuspäiväkirja. Nevertheless, the inherent optimism at the core of self-help still reigns supreme—globally as well as in Finland.

Self-Help in Finland

Since this thesis concerns itself with self-help in the context of the Finnish market, it is important to further expand upon how these books came to be popular here, and how they are used today. Here, like in much of the world, self-help was in steady (but not great) demand for many decades before experiencing a boom in the past few. Between 1990 and 2000, the amount of works filed under the categories ‘life skills’ and ‘life management’ in the Finnish National Bibliography Fennica tripled (Salmenniemi & Pessi, 2017). Self-help titles currently consistently top the yearly nonfiction bestseller lists, and their popularity is ever-increasing (Salmenniemi & Pessi, 2017).

Originally, self-help made its way to Finland in the form of international bestsellers that were imported and translated, usually from English (Hallamaa, 2011). Journalist Hannu Hallamaa points to businessman Jari Sarasvuo’s 1996 book Sisäinen sankari as the starting point for our homegrown self-help (2011). Hallamaa notes that Sarasvuo, among other popular Finnish self-help authors, works as a business coach, and states that the line between commercial coaching and self-help is often blurry here (2011). This invites the interpretation that early Finnish self-help was harnessed to benefit the world of business as much as the readers themselves. In the decade that has passed since the publication of Hallamaa’s text, the field has grown and diversified greatly. In a more recent article, Miia Gustafsson (2017) quotes Otava’s lead editor Mari Mikkola, who states that American self-help guides are no longer in vogue with consumers, who are instead looking for insight from closer to home: “Nyt kotimaisuus on valttia. Meillä on omasta takaa huippuasiantuntijoita, jotka kirjoittavat omasta alastaan”. [Being domestic is an asset right now. We have our own experts, who write about their respective fields.] As evidenced by the difference in approach (leaning towards ‘culture-optimism’) and the demand for domestic literature, the Finnish self-help market is clearly a separate entity from its American cousin. The influence of contemporary American works cannot, however, be discounted.

Researchers have drawn parallels between self-help’s developments in Finland and the United States, noting the connection between ideological changes in society and the self being seen as a ‘project’ that each of us has a responsibility to work on (Salmenniemi & Pessi, 2017). Suvi Salmenniemi lists three main reasons for self-help’s current success in Finland. Firstly, she mentions changes in the working world. Increasingly often, an individual’s professional success is not only determined by their schooling or experience, but also by their personality. Many self-help books offer sought-after guidance on creating a personal brand and selling it to others to get ahead (Hallamaa, 2011). Secondly, she brings up the slow crumbling of our Nordic welfare state. When Finns cannot rely as much on social security, they turn instead to books in their times of need (Hallamaa, 2011). Lastly, she speaks of the fundamental changes that the Finnish society has seen in the past fifty-odd years, moving from a collectivist culture to a more individualistic one. Many modern self-help books have fitting core tenets: the problems people face are of their own doing, and so it follows that the primary way to fix them is to develop oneself (Hallamaa, 2011). This puts intense pressure on the individual. As previously stated, modern self-help can go so far as to blame their readers for the issues they face, citing “a negative attitude” or “erroneous ways of thinking”, while disregarding the impact of outside forces such as societal power dynamics (Salmenniemi & Pessi, 2017). This, combined with the general competitiveness of today’s society, can have devastating consequences for readers’ mental health. Finnish writer Eeva Kolu discusses this in her popular book Korkeintaan vähän väsynyt. Kolu asserts that the constant pressure for young Finnish women to perform and outdo themselves has led to a collective burnout (2020). She mentions writing-based self-help as a contributing factor, or at least a symptom of the disease, in this sarcastic quote from the book (2020, p. 30):

- “Tavoitteiden asettaminen on ajan henki. #GOALS. Kirjakaupat tursuavat tehtäväkirjoja, jotka auttavat omien tavoitteiden määrittelyssä, ja oppaita, jotka kertovat miten ne saavutetaan. Aina on oltava maali, jota kohti kulkea. Kuka enää lenkkeilee, kun voi treenata puolimaratonille?” [Goal-setting is the zeitgeist. #GOALS. Bookstores are full of assignment books that help you define your goals and guides that tell you how to reach them. We must always have a target to strive towards. Why go jogging these days, when you can train for a half marathon?]

A Globalized Presence

Society is constantly in flux, hence self-help content is constantly in demand. The Western way of life has changed markedly from what it was just two or three decades ago, and people are desperate for guidance and encouragement in the face of their new realities. Every so often, new (or freshly repackaged) ideas spark national or global trends, but not all sought-after advice comes from recent publications. Self-help, depending on the work you view it through, is both a mirror of our current time and a window to the past. Several self-help texts that were written hundreds if not thousands of years ago are still read, quoted, and studied extensively. Confucius’ teachings (or Confucianism) are still highly relevant in China; some go as far as to call them “the defining characteristic of Chinese mentality” (Yang, 2017, p. 184). Sun Tzu’s The Art of War has become a favorite among Western business writers, who view its teachings through the lens of capitalism (McCann, 2012). And in an interesting mirroring of the Western popularity of The Art of War, Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations has recently become a national bestseller in China after the country’s former Premier Wen Jiabao revealed that he has read it over one hundred times (Li, 2013). Contentually, a common thread of idealism, confidence, and introspection can be traced through much of self-help’s history, with new books bringing their “own generational edge to the same fundamental idea” (Manson, 2015). Conceptually, the neatly organized Victorian etiquette manuals can be viewed as stylistic predecessors to modern self-help books, which tend to utilize a structured, often list-based, format. The ripples of the literary past can be felt to this day.

Still, self-help has evolved greatly during its existence. Nowhere is that more evident than with its societal positioning. Before Smiles’ time, self-help books were intended for a very small audience: the upper crust. They were read much more widely, of course, but their authors did not expressly aim to benefit the general populace. Slowly, the genre became more accessible. Some scholars even argue that it has undergone a reversal of sorts. Its growing popularity among the masses correlates with its rejection by the elite. Beth Blum illustrates the shunning of self-help from academic spheres through the reluctance of top American universities to let the genre’s giant Dale Carnegie host lectures on their premises. She writes: “His practice of liberal copying and unsignaled paraphrase was at odds with the originality and propriety prized by institutional academic culture” (2020, p. 3). This exclusion was not the coup de grâce that scholars might have imagined at the time. Blum goes so far as to argue that the elitism of intellectual literary circles might be what created the demand for self-help in the first place: “Though reading for improvement has fallen into disfavor among academics, self-help provides a medium through which individuals can pursue self-betterment unfettered” (2020, p. 7). The genre remains in high demand. Currently, it is one of the most profitable genres of literature, with 150 new titles published each week (Blum, 2020).

The reversal of the genre’s target social class is not the only noticeable change in direction. In stark contrast to much of their history, the self-help books of our time seem to largely be written and read by women (e.g., Blum, 2020). In Finland today, many books are marketed specifically towards women, and they are most commonly bought by middle-aged women (Gustafsson, 2017). In other words, assisted self-improvement of a mental nature seems to currently primarily interest a female audience. This is logical. As previously stated, people chiefly turn to self-help in times of great personal and societal upheaval. Women’s position in Western societies has undoubtedly evolved much more than men’s during the past century—increasingly rapidly so in the past few decades. Arguably, women currently face a more confusing reality than men, one where new ideals are constantly vying with old ones. Consequently, their need for spiritual guidance is more acute. Writer Jennifer Wilson gives an example: “Self-help has resonated particularly with women, for whom focusing on the self can be a defiant protest against the self-sacrificing expectations of motherhood” (2020). Wilson argues that despite its current highly commercial nature, self-help still serves the same age-old purpose for some: acting as a catalyst for social change.

Indeed, in contrast to its station and target demographic, the reasons for consuming advice literature have not changed greatly over time. Much like in Samuel Smiles’ Victorian Britain, it is the “promises of transformation, agency, culture, and wisdom”, Beth Blum argues, that attract modern readers to self-help (2020, p. 7). Today, the genre benefits from its breadth and diversity. Specific works may have a clearly defined target audience, but self-help is, by its very nature, trying to reach different kinds of people—couples, singles, divorcées; dieters, bingers, bon vivants; businesspeople, bohemians, the unemployed—with books tailored to their particular needs. Often, these needs transcend time and culture. Despite primarily capturing the spirit of its place of origin, self-help in its modern form has always been read by a varied, international audience. Beth Blum describes the genre as a “globalized presence” and writes: “Self-help has become a transmedia industry that implicates us all—aesthetes and entrepreneurs, critics and lay readers—in its expanding cultural matrix” (2020, p. 44).

As this overview of the genre has illustrated, self-help has a rich and far-reaching history. Its ubiquity points to humans’ innate need for personal development and enlightenment, and for sharing our insights on these topics with others. As our societies and attitudes have evolved, so have the books that reflect and display them. An interesting thing to note, however, is that society has not always viewed these books similarly. A constant ebb and flow can be seen, with pivotal works and hard times sparking an intense interest in the genre, only for it to subside some time later. We are currently living in another golden era of self-help. A clear shift in attitude is visible in the last decade or so, during which self-help books have gone from being an openly ridiculed ‘last resort’ for the truly desperate to being accepted as legitimate tools for self-exploration and - betterment. One reason is undoubtedly how interconnected the world has become. It has never been easier to weigh and to measure one’s life against others’, and to consequently find it wanting. The rise of so-called influencers—the expertly airbrushed ambassadors of a happy, sugar-coated life—on social media outlets like Instagram and TikTok has paved the way for our current myopic focus on perfecting ourselves and our lives. The current Western culture is clearly one of self-optimization, and self-help is its mouthpiece. As Alexandra Schwartz writes in The New Yorker (2018):

- “We must now chart our progress, count our steps, log our sleep rhythms, tweak our diets, record our negative thoughts—then analyze the data, recalibrate, and repeat. [...] We are being sold on the need to upgrade all parts of ourselves, all at once, including parts that we did not previously know needed upgrading.”

It is no wonder that many look for guidance with this metamorphosis. That is the appeal of self-help. Of course, as the likes of Ad Bergsma (2007) and Beth Blum (2020) have noted, the genre is not universally adored. Its critics maintain that self-help authors first create illusory voids in our lives and then rush to fill them with their advice—for a suitable price, of course. Clever ruse or not, the works’ appeal and success cannot be denied. They are being read by innumerable people around the world, and this is unlikely to change, since the human race will not soon run out of things to aspire to. This means that all aspects of them should be critically examined. Unfortunately, the genre has heretofore largely been overlooked by academics. The reasons for this will be further expanded upon in the next section.

Sources for Chapter 2

BOOKS

Ashley, K., & Clark, R. L. A. (Eds.). (2001).

Medieval Conduct: Texts, Theories, Practices.

University of Minnesota Press.

Blum, B. (2020). The Self-Help Compulsion:

Searching for Advice in Modern Literature.

Columbia University Press.

Castiglione, B. (1901). The Book of the Courtier.

(L. E. Opdycke, Trans.) Original work published

in 1528. Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Dolby, S. K. (2005). Self-Help Books:

Why Americans Keep Reading Them.

University of Illinois Press.

Fairbanks, D. (1917). Laugh and Live.

Britton Publishing Company.

Kolu, E. (2020). Korkeintaan vähän väsynyt,

eli kuinka olla tarpeeksi maailmassa,

jossa mikään ei riitä. Gummerus.

Krueger, R. L. (2009). Preface. In Johnston, M.

(ed.) Medieval Conduct Literature: An Anthology

of Vernacular Guides to Behaviour for Youths

with English Translations (77th ed., Vol. 111).

University of Toronto Press.

Marden, O. S. (1911). Pushing to the Front.

The Success Company.

Smiles, S. (1897). Self-Help; with illustrations

of Conduct and Perseverance (Popular Edition).

John Murray.

Starker, S. (1989). Oracle at the Supermarket:

The American Preoccupation with Self-Help

Books. Transaction Publishers.

JOURNALS & MAGAZINES

Allen, G. (2019). Mirrors for Secretaries: The

Tradition of Advice Literatureand the Presence

of Classical Political Theory in Italian Secretarial

Treatises.Laboratoire Italien (Online), 23.

Bergsma, A. (2007). Do self-help books help?

Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 341–360.

Bricklin, J. (2014). Success Story: Businessman

and Entrepreneur Orison Swett Marden.

Financial History, 109, 26–29.

Dahmer, C. (2016). “Still, however, it is

certain that young ladies should be more apt

to hear than to speak”: Silence in Eighteenth

Century Conduct Books for Young Women.

XVII-XVIII, 73, 123–145.

Ker, J. (2000). The Inner Citadel: The

Meditations of Marcus Aurelius. Journal of

the History of Philosophy, 38(1), 116–118.

Kleidosty, J. (2018). Māwardī and Machiavelli:

Reflections on Power in Their Mirrors for Princes.

Philosophy East & West, 68(3), 721–736.

Lovett, F. (2012). The Path of the Courtier:

Castiglione, Machiavelli, and the Loss of

Republican Liberty. The Review of Politics,

74(4), 589–605.

Martines, L. (1997). Review: The Fortunes

of the Courtier: The European Reception of

Castiglione’s Cortegiano by Peter Burke.

The American Historical Review, 102(4), 1148.

McCann, D. (2012). On Reading Sun-Tzu:

The Promise And Perils Of Appropriating

A Chinese Classic In International Business

Ethics. Journal of International Business Ethics,

5(2), 27-37, 56.

Morris, R. J. (1981). Samuel Smiles and the

Genesis of Self-Help; the Retreat to a Petit

Bourgeois Utopia. The Historical Journal,

24(1), 89–109.

Richards, J. (1982). Spreading the Gospel of

Self-Help: G.A. Henty and Samuel Smiles.

The Journal of Popular Culture, 16(2), 52–65.

Salmenniemi, S., & Pessi, A. B. (2017).

“Herätkää pöljät!”: Minuus, yhteiskunta ja

muutos self-help-kirjallisuudessa.

Kulttuurintutkimus, 34(1).

Song, J., & Jiao, X. (2018). Confucius’ Junzi:

The conceptions of self in Confucian. Educational

Philosophy and Theory, 50(13), 1171–1179.

The Economist. (2004). On the origin of

self-help. 371(8372), 86.

The Economist. (2013). How to succeed.

409(8860), 90.

Weller, T. (2014). The Puffery and Practicality

of Etiquette Books: A New Take on Victorian

Information Culture. Library Trends,

62(3), 663–680.

Yang, J. (2017). Virtuous power: Ethics,

Confucianism, and Psychological self-help in

China. Critique of Anthropology, 37(2), 179–200.

ONLINE SOURCES

Burdon, E. S. (2020). Do This One Thing

To Be Happier Every Single Day. Medium.

Cambridge. (n.d.). Definition of self-help.

Cambridge Dictionary.

Collins. (n.d.). Definition of self-help.

Collins Dictionary.

Connor, L. (2021). Psychologists say toxic

positivity is on the rise – but what is it and

why is it harmful? The Independent.

Corrigan, M. (2013). “Self-Help Messiah” Dale

Carnegie Gets A Second Life In Print. NPR.

Cutruzzula, C. (2016). The Last 100 Years

of Self-Help. Time.com.

Goodreads. (2022a). Toxic Positivity.

Quotes by Whitney Goodman. Goodreads.

Goodreads. (2022b). Good Vibes, Good Life.

Quotes by Vex King. Goodreads.

Gustafsson, M. (2017). Hyvinvointikirjat ovat

kasvava bisnes – suorittaminen ei enää käy,

nyt haetaan henkistä voimaa. Yle Uutiset.

Hallamaa, H. (2011). Osta parempi elämä.

Ylioppilaslehti.

Lamb-Shapiro, J. (2013). A Short History of

Self-Help, The World’s Bestselling Genre.

Publishing Perspectives.

Manson, M. (2015). The Staggering Bullshit

of ‘The Secret.’ Observer.

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.-a). Definition of

self-help. Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.-b). Definition of

machiavellian. Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

Schwartz, A. (2018). Improving Ourselves

to Death. The New Yorker.

Weiler, B. (2015). Mirror for Princes.

Encyclopedia Britannica.

Wilson, J. (2020). The Radical Origins of

Self-Help Literature. The Nation.